Introduction

When Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) collapsed in March 2023, headlines focused on panic-driven withdrawals and the speed of a modern bank run. Depositors rushed to pull funds, and the bank’s liquidity evaporated almost overnight.

But beneath the surface, the seeds of failure were visible in the numbers long before the final week. This case study asks a simple question: could a disciplined investor, grounded in valuation and accounting basics, have spotted the red flags before the collapse?

The answer is yes. And the proof was hiding in plain sight — in SVB’s financial statements, disclosures, and footnotes.

1. Valuation Framework Recap

At its core, valuation is the present value of future cash flows. In practice, investors rely on proxies—ratios and multiples derived from financial statements.

For banks, common measures include:

- Price-to-Book (P/B): assets like loans and securities are the lifeblood of banks.

- Net Interest Margin (NIM): the spread earned on loans versus deposits.

- Capital Ratios (Tier 1, CET1): cushions against shocks.

These numbers are useful, but they are products of accounting choices—not immutable truths. SVB’s story begins here.

2. The Balance Sheet Problem

By late 2021, SVB looked strong:

- Deposits tripled during the tech boom (from ~$61B in 2019 to ~$189B in 2021).

- Total assets grew in parallel.

Instead of lending, SVB parked much of those deposits in long-term U.S. Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities.

SVB Assets Breakdown (2019–2022)

| Year | Securities (% of Total Assets) | Net Loans & Leases (% of Total Assets) |

|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 39.68% | 46.96% |

| 2020 | 41.67% | 39.29% |

| 2021 | 60.07% | 31.57% |

| 2022 | 56.12% | 35.22% |

On the surface, Treasuries seem safe—but accounting treatment made all the difference. Held-to-Maturity (HTM) securities were booked at cost, not market value. Rising interest rates crushed the market value of these bonds. Because they were HTM, losses didn’t hit income statements or book value—only a disclosure in the footnotes.

3. Footnotes Reveal

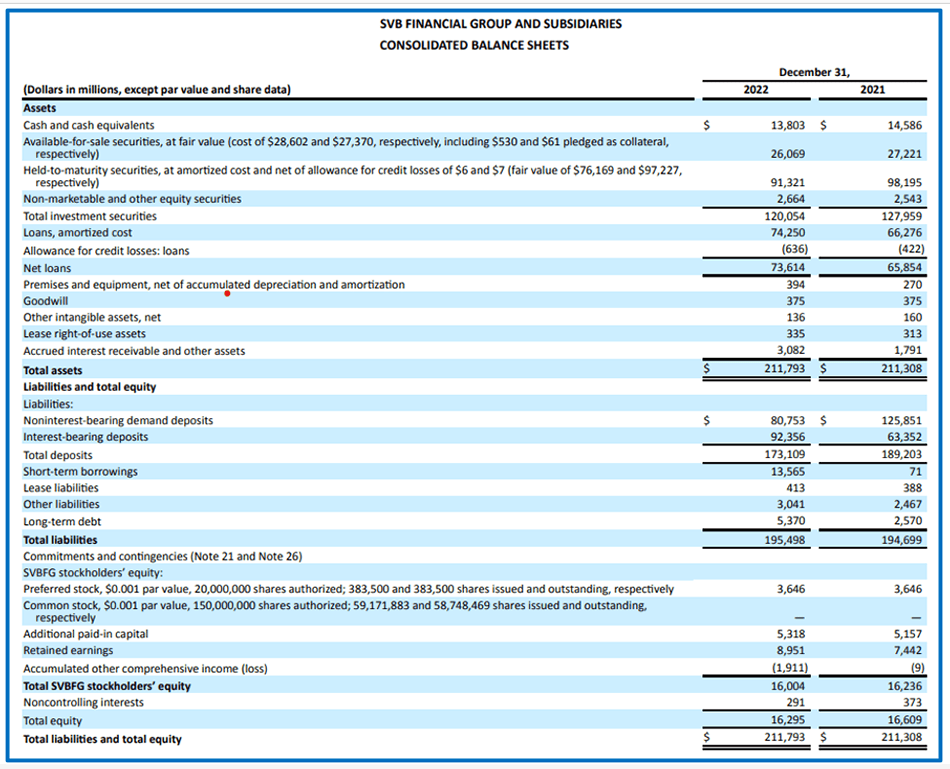

In its 2022 10-K filing, Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) reported $91.3 billion in Held-to-Maturity (HTM) securities at amortized cost. However, the fair value of these securities was only $76.2 billion, resulting in an unrealized loss of approximately $15.1 billion. This discrepancy was disclosed in the footnotes, specifically on page 125 of the filing.

This unrealized loss was not reflected in SVB’s reported book equity, which stood at $16.3 billion at year-end 2022. Had these HTM securities been marked to market, the bank’s equity would have been reduced to around $1.2 billion, assuming no tax benefits.

The HTM classification allowed SVB to exclude these unrealized losses from its balance sheet, effectively masking the true financial health of the institution. This accounting treatment has been a focal point in discussions about the transparency and reliability of financial reporting for banks.

The footnote disclosure was a critical piece of information that, if more widely recognized and understood, might have alerted investors and regulators to the underlying risks SVB was facing. This case underscores the importance of scrutinizing financial statement footnotes to uncover potential financial issues that may not be immediately apparent from the primary financial statements.

In plain English:

- Book equity looked strong on the surface (~$16B).

- But mark-to-market, equity was close to zero.

- The bank was a rising-rate time bomb.

This was a textbook case of why accounting ≠ economic reality.

4. Multiples Misled Investors

Commonly used valuation shortcuts hid the risks:

- P/B ratio: ~1.2x in 2021, stable

- Earnings growth: strong due to low funding costs

- Capital ratios: compliant with regulatory minimums

But these multiples relied on accounting that masked economic losses. Adjusted for HTM fair-value losses, SVB was effectively insolvent well before March 2023.

Key takeaways:

- Valuation multiples are shorthand, not absolute truth. P/B, P/E, and P/S only make sense when the underlying accounting is interrogated.

- Footnotes matter. The $15B unrealized loss was critical but widely ignored.

- Accounting rules shape perception. HTM vs. AFS classification wasn’t technical—it was the difference between appearing solvent on paper and being insolvent in reality.

Conclusion

Could SVB’s collapse have been predicted? Not with perfect timing. But the direction was visible to anyone willing to bridge valuation and accounting.

The lesson:

- Accounting is the language of business—understand it before buying stocks or bonds.

- Valuation isn’t memorizing ratios; it’s interpreting the story numbers tell and spotting when they might be misleading.

- Footnotes and disclosures are more important than headline figures.

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Next up we will talk about some basics of Bonds Valuation.

Leave a reply to Anonymous Cancel reply