Series: How to Read a Bond Indenture — A Value Investor’s Framework

Introduction

Most investors assume default is a single moment:

The company misses a payment.

Bondholders take control.

Recovery begins.

That assumption is wrong.

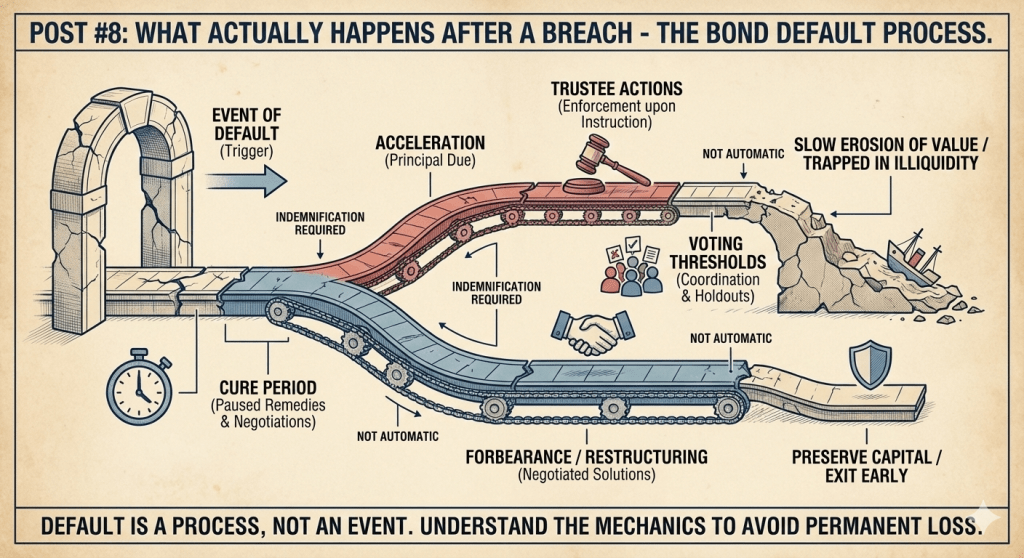

In reality, default is a process, not an event. It unfolds through notices, cure periods, voting thresholds, trustee actions, and legal constraints — all pre-defined in the indenture.

Understanding how default actually works often determines whether a bondholder:

- Exits early

- Preserves capital

- Or gets trapped in a slow erosion of value

This post explains what really happens after a breach — not in theory, but in contractual reality.

1. What Is an Event of Default? (EOD)

An Event of Default is a contractually defined trigger that allows bondholders to enforce remedies.

Not all problems are defaults.

Not all defaults are immediately enforceable.

Indentures distinguish between:

- Events of Default

- Events of Potential Default

- Technical breaches with cure rights

Understanding that distinction is critical.

2. The Most Common Events of Default

A. Payment Default

Failure to:

- Pay interest

- Repay principal

- Make sinking fund payments

These are usually:

- Subject to a short grace period (5–30 days)

- Clear and unambiguous

Payment defaults are the strongest triggers.

B. Covenant Default

Failure to comply with:

- Negative covenants

- Affirmative covenants

- Reporting requirements

These often include:

- Notice requirements

- Cure periods (30–90 days)

- Remedial actions

Covenant defaults rarely lead to immediate acceleration — but they signal deterioration.

C. Cross-Default/ Cross-Acceleration

Triggers default if:

- Other material debt defaults or accelerates

Strong versions:

- Low dollar thresholds

- Broad debt definitions

Weak versions:

- High thresholds

- Exclusions for subsidiaries or secured debt

This determines how quickly distress spreads.

D. Bankruptcy or Insolvency

Includes:

- Bankruptcy filings

- Insolvency proceedings

- Assignment for benefit of creditors

These typically trigger automatic acceleration.

E. Judgment Defaults

Large court judgments not paid within a specified period can trigger default.

Often overlooked but critical in litigation-heavy industries.

3. Cure Periods: Why Defaults Are Not Immediate

Most defaults include a cure period:

- Time allowed for the issuer to fix the breach

- Prevents technical defaults from causing chaos

Examples:

- Late filing of financials → 60 days to cure

- Covenant breach → 30–90 days to restore compliance

During cure periods:

- Bonds may sell off

- But legal remedies are paused

Sophisticated investors watch cure clocks, not headlines.

4. Acceleration: When Principal Becomes Due

Acceleration means:

The entire outstanding principal becomes immediately payable.

Acceleration is not automatic in most cases.

How Acceleration Occurs

- Typically requires a vote (often 25%–50% of holders)

- Initiated through the trustee

- Can be reversed if defaults are cured

Why Acceleration Is Rare

- It can force bankruptcy

- It reduces restructuring flexibility

- It may destroy residual value

Bondholders often prefer negotiation to acceleration.

5. The Trustee: Pwer, Limits, and Reality

Bondholders do not act individually.

They act through a trustee.

What the Trustee Does

- Receives default notices

- Represents bondholders collectively

- Enforces remedies upon instruction

- Manages legal actions

What the Trustee Does NOT Do Automatically

- Monitor issuer behavior proactively

- Declare defaults without direction

- Act unless indemnified

Trustees are administrative agents, not activist defenders.

Trustee Indemnification Clause (Critical Detail)

Most indentures require:

Bondholders to indemnify the trustee against costs before action is taken.

This means:

- Small holders lack influence

- Action requires coordination

- Delay is common

Default enforcement is slow by design.

6. Holder Voting Thresholds: Who Controls the Outcome

Indentures specify voting thresholds for:

- Acceleration

- Waivers

- Amendments

Typical thresholds:

- 25% → Declare default / accelerate

- 50%+ → Direct trustee actions

- 66⅔% → Amend core terms

This creates:

- Coordination problems

- Holdout power

- Strategic behavior among creditors

Bondholders do not move as one unit.

7. Why Many Defaults don’t Lead to Immediate Recovery

Even after default:

- Interest may continue to accrue

- Negotiations can last months or years

- Recoveries depend on asset value, not legal rights

Common outcomes:

- Forbearance agreements

- Amend-and-extend deals

- Debt exchanges

- Out-of-court restructurings

Default ≠ cash recovery.

8. Real-World Pattern: The Slow Default

Many distressed credits experience:

- Covenant breach

- Cure extension

- Waiver negotiations

- Rating downgrade

- Price decline

- Exchange offer

- Eventual restructuring

Bondholders who understand the process:

- Exit earlier

- Preserve capital

- Avoid illiquid endgames

Those who don’t:

- Hold too long

- Rely on legal myths

- Suffer permanent loss

9. Practical Default-Section Checklist

When reading the EoD section, identify:

- What constitutes default

- Grace periods

- Cure rights

- Acceleration thresholds

- Trustee obligations

- Indemnification clauses

- Voting requirements

- Amendment mechanics

Ask yourself:

How fast can I act — and how hard is it to act?

10. Value Investor Interpretation

Default is not a cliff.

It is a slope.

The bond indenture determines:

- How steep the slope is

- Who controls the descent

- Whether exits exist before free fall

Value investors win in credit by:

- Anticipating stress

- Respecting structure

- Acting early — not legally, but economically

Conclusion

Most bond investors lose money not because they misunderstand yield but because they misunderstand process.

Events of Default do not guarantee protection.

They only define who may act, when, and at what cost.

If you don’t know those rules, you are not protected you are merely hopeful.

Leave a comment