Series: How to Read a Bond Indenture — A Value Investor’s Framework

Introduction

Most of a bond indenture describes normal times.

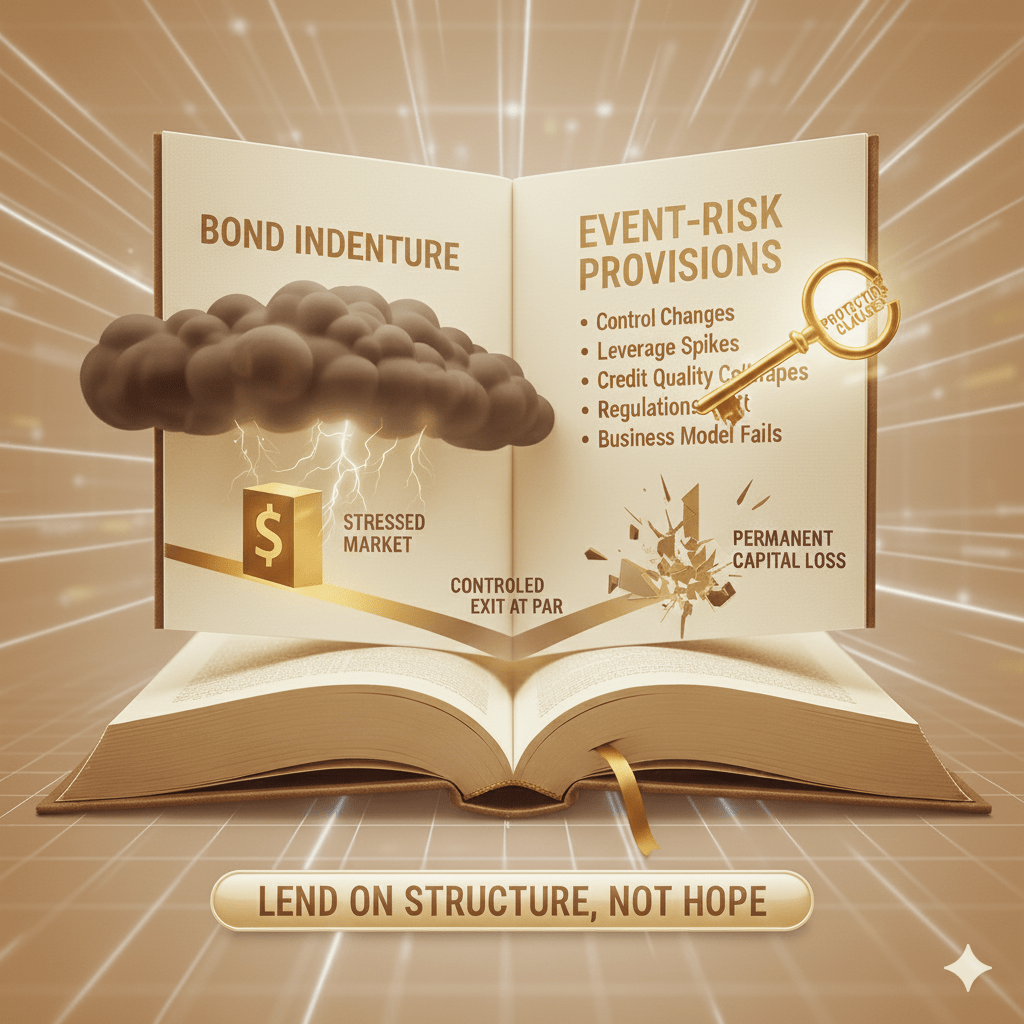

Event-risk provisions exist for abnormal times.

They activate only when:

- Control changes hands

- Leverage spikes

- Credit quality collapses

- Regulations shift

- The business you underwrote no longer exists

These clauses are rarely discussed in bull markets. But in stressed markets, they often determine whether a bondholder exits at par or rides the position into permanent capital loss.

If you skip this section of the indenture, you are underwriting the company only in the world you hope exists — not the one that actually occurs.

1. What Is “Event Risk”?

Event risk refers to non-operational shocks that radically alter the issuer’s risk profile without immediately triggering default.

Examples:

- Leveraged buyouts

- Mergers and acquisitions

- Private-equity recapitalizations

- Asset carve-outs

- Ratings downgrades

- Regulatory or tax changes

These events can:

- Increase leverage overnight

- Subordinate existing creditors

- Strip assets from the balance sheet

- Transfer risk from equity to debt

The bond indenture anticipates this — if it is well written.

2. Change-of-Control (COC): The Single Most Important Event Clause

A Change-of-Control Put allows bondholders to force the issuer to repurchase the bond usually at 101%–103% of par if control of the company changes.

Why This Exists

Acquirers often:

- Use leverage to finance acquisitions

- Push debt onto the target’s balance sheet

- Weaken credit metrics post-deal

Without a CoC put, bondholders are dragged into a new capital structure they never agreed to.

What Qualifies as a Change of Control?

Definitions vary, but typically include:

- More than 50% ownership change

- Merger resulting in loss of voting control

- Sale of substantially all assets

- Change in board control

Key detail:

Some CoC clauses only trigger if:

- A ratings downgrade occurs after the change

This is materially weaker protection.

Strong vs Weak CoC Clauses

| Feature | Strong Protection | Weak Protection |

|---|---|---|

| Trigger | Ownership change alone | Ownership + downgrade |

| Repurchase Price | 101–103 | Par |

| Timing | Immediate | Delayed |

| Coverage | All bondholders | Limited |

If a CoC clause requires a downgrade, the investor is exposed to ratings agency discretion, not contractual certainty.

3. Ratings Triggers: The Illusion of Protection

Some bonds contain clauses tied to:

- Moody’s

- S&P

- Fitch

These may:

- Increase coupon

- Require collateral posting

- Trigger redemption

Why These Are weak

Ratings agencies:

- React slowly

- Lag real deterioration

- Are not legally accountable to bondholders

A bond that relies on ratings triggers rather than structural protections is outsourcing risk management to a third party.

Professional investors prefer:

- Hard leverage tests

- Change-of-control puts

- Asset and lien protections

Ratings triggers can help — but they should never be the primary defense.

4. Tax & Regulatory Event Clauses

These allow issuers to redeem bonds if:

- Tax laws change

- Withholding taxes are imposed

- Regulatory capital treatment shifts

Issuer Benefit

- Allows clean refinancing if regulations turn hostile

Investor Risk

- Early redemption at par

- Forced reinvestment at inferior yields

These clauses are common in:

- Bank capital instruments

- Cross-border bonds

- Hybrid securities

If present, investors must price them as issuer-favorable call options.

5. Asset Carve-Outs & Spin-Off Risk

Some indentures allow:

- Asset sales into unrestricted subsidiaries

- Spin-offs without bondholder consent

- Transfer of profitable divisions

This is event risk disguised as corporate flexibility.

Red flags include:

- Broad definitions of “Permitted Asset Transfers”

- No mandatory debt repayment from proceeds

- No bondholder put option on spin-off

This is how:

Credit quality deteriorates legally, not operationally.

6. Cross-Default vs Cross- Acceleration

These clauses determine how defaults propagate across a capital structure.

Cross-Default

- A default on one debt triggers default on others immediately

Cross-Acceleration

- Only triggers if the other debt is accelerated

Cross-acceleration is weaker protection.

Strong indentures include:

- Low dollar thresholds

- Broad inclusion of material debt

Weak indentures:

- High thresholds

- Exclusions for “non-recourse” or subsidiary debt

7. Leveraged Buyouts Without CoC Protection

Historically, many LBOs harmed bondholders not through default but through structural repricing of risk.

Bondholders experienced:

- Higher leverage

- Reduced asset coverage

- No exit mechanism

When CoC protection exists, bondholders can:

- Exit at a premium

- Reallocate capital

- Avoid being involuntary lenders to a private-equity structure

The difference is contractual, not analytical.

8. How to Read the Event Risk Section (Practical Checklist)

When you reach this part of the indenture, identify:

- Change-of-control definition

- Repurchase price

- Downgrade requirements

- Ratings trigger mechanics

- Tax/regulatory redemption clauses

- Asset transfer permissions

- Cross-default thresholds

- Subsidiary exclusions

Ask one question:

Can my risk profile change materially without my consent?

If the answer is yes, demand yield compensation — or walk away.

9. Value Investor Interpretation

Event risk clauses exist because:

Markets do not fail gradually — they fail discontinuously.

Operational metrics deteriorate slowly.

Capital structures change overnight.

The value investor’s advantage in credit comes from:

- Anticipating discontinuities

- Insisting on contractual exits

- Refusing to underwrite management optionality for free

A bond without event-risk protection is not conservative —

it is fragile.

Conclusion

Most bond losses do not occur because companies fail slowly.

They occur because structures change quickly.

Event-risk clauses are the last line of defense between:

- A controlled exit at par

- And a forced ride into distress

If you don’t read this section, you are lending on hope and not structure.

Next in the Series

Post #7 — Guarantees, Subsidiaries & Structural Subordination: Who Actually Owes You the Money

We’ll break down:

- Parent vs subsidiary guarantees

- HoldCo vs OpCo debt

- Why “senior” can still be structurally junior

- How recovery pools are really formed

Leave a comment