Series: How to Read a Bond Indenture — A Value Investor’s Framework

Introduction

Most investors focus almost exclusively on coupon income when evaluating a bond. But the most important part of the credit equation is often the return of principal, not the return on principal.

How a bond repays its principal affects:

- Default risk

- Loss-given-default

- Reinvestment risk

- Duration

- The true economic yield

This structure is defined in the sinking fund, amortization, and redemption mechanics embedded in the indenture.

Understanding these features enables you to see what most retail investors miss:

Some bonds naturally de-risk over time. Others concentrate default risk at one single point.

That difference is structural, not accidental.

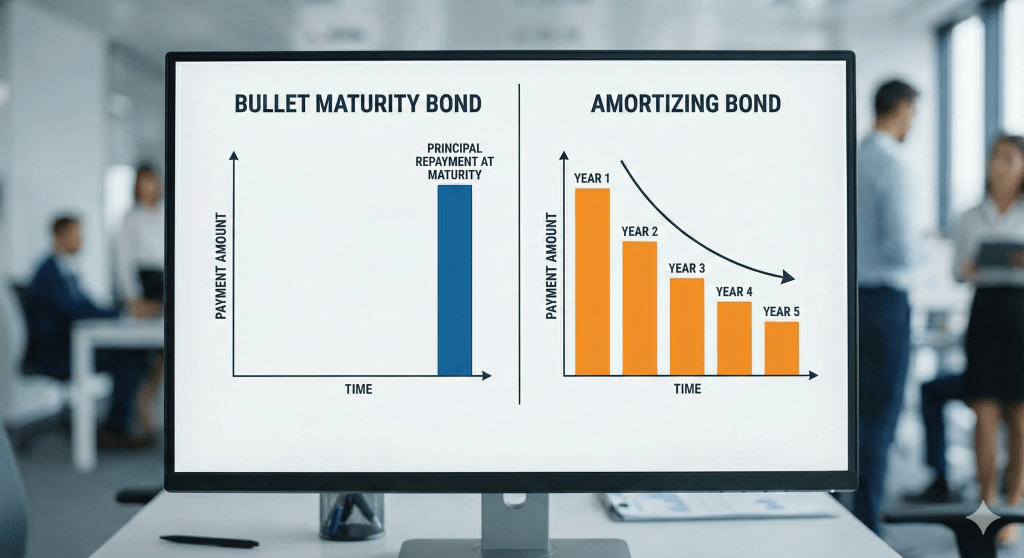

1. Bullet Maturity vs. Amortizing Bonds

Let’s start with the two core repayment structures.

A. Bullet Maturity (Most Corporate Bonds)

This is the simplest structure:

- Coupons paid annually or semi-annually

- 100% of principal paid back at final maturity

- No principal payments before that date

Risk Profile:

- Default risk is back-loaded

- Loss severity is high if the issuer fails near maturity

- Duration remains high until the very end

This is the standard structure for most:

- Corporate bonds

- High-yield issues

- Investment-grade notes

- Senior unsecured debt

Value Investor Interpretation:

Bullet maturities are the purest expression of credit risk. This is because all principal sits exposed until the final day.

B. Amortizing Bonds

Amortizing structures repay a portion of principal every year, similar to a mortgage.

For example:

- 10% principal redemption each year

- Equal principal payments

- Or customized amortization schedules

Risk Profile:

- Default risk declines annually

- Loss severity is materially lower because capital is returned earlier

- Duration shrinks over time

Amortizing bonds are common in:

- Project finance

- Infrastructure

- Utilities

- Asset-backed securities

- Certain municipal bonds

Value Investor Interpretation:

Amortization is a built-in risk reducer — but it introduces reinvestment risk.

2. Sinking Funds: The Hybrid Structure (Most Misunderstood Feature in Credit)

A sinking fund sits between bullet maturity and full amortization.

It requires the issuer to retire a fixed percentage or amount of bonds annually (or periodically) before the final maturity.

How a Sinking Fund Works

Example:

- $500M bond issue

- 10-year maturity

- Sinking fund beginning year 5

- Redeem 5% of principal each year

The issuer may:

- Redeem bonds at par

- Or purchase them in the open market at or below par

- Or randomly select bond certificates to retire

This structure spreads principal repayment over time.

3. Why Sinking Funds Matter (The Credit Investor’s View

A. Reduction in Default Exposure

A sinking fund reduces the principal outstanding as the bond ages.

This means:

- Lower exposure as financial conditions evolve

- Lower loss severity if the issuer defaults late in life

- Improved recovery prospects

Bondholders tend to be structurally safer with a sinking fund than with a pure bullet maturity.

B. But There’s a Hidden Drawback: Reinvestment Risk

Every principal payment returned early must be reinvested.

If rates fall during the life of the bond:

- You get cash back at par

- But cannot reinvest at the original yield

- Your portfolio yield naturally declines

This matters especially for long-term investors.

Conclusion:

A sinking fund is both a risk reducer and a return reducer — depending on the macro environment.

C. Issuer Optionality

If the indenture gives the issuer flexibility, they may:

- Repurchase bonds in the open market when prices are below par

- Redeem at par when open-market prices are above par

This is an embedded option:

- Favorable to issuer

- Neutral to slightly negative for bondholders

4. Random Redemption Risk (The Retail Investor Trap)

Many investors forget a key detail:

When a sinking fund redemption occurs, individual bonds may be randomly selected for redemption.

This means your bond could be:

- Redeemed early (shorter duration)

- Or not redeemed early (longer exposure)

Your actual return path becomes uncertain.

Your duration becomes a range rather than a defined number.

Professional bond desks model this using:

- Conditional prepayment rates

- Scenario-weighted duration

Retail investors rarely do.

5. How Sinking Funds Interact with Calls

This is where structures become complex.

Three common interactions:

A. Callable + Sinking Fund (Common in High-Yield)

- The sinking fund slowly reduces principal

- Remaining balance is callable at issuer’s option

This often leads to:

- Issuer buying back cheap in early years

- Calling the rest when refinancing becomes attractive

B. Make-Whole Call + Sinking Fund

- More investor-friendly

- Issuer must pay present-value economics for early redemption

C. No Call+ Sinking Fund (Investor-Friendly)

- Rare

- Significantly reduces duration and credit exposure

6. Air Canada 4.625% 2029

Note: This is an illustrative example — you can substitute any real sinking fund security for the post on your site.

Air Canada once issued bonds with:

- A sinking fund starting in year 6

- 10% annual principal redemptions

- Optional issuer open-market purchases

This created:

- Declining credit exposure

- Shortening duration

- Moderate reinvestment risk

- Higher investor protection vs a bullet maturity

Credit analysts priced this bond using:

- Yield-to-average-life

(because maturity is uncertain)

Retail investors often priced it incorrectly using:

- Yield-to-maturity

(which overstated return)

7. Reading the Indenture: What to Look For

In the Sinking Fund / Redemption section of the indenture, locate:

- Start date

- Percentage or dollar amount to retire per period

- Whether purchases may be made on the open market

- Whether the issuer may accelerate sinking fund payments

- Whether redemptions are random

- Whether redemptions occur at par or with a premium

- Interaction with any call features

- Whether “double up” payments are allowed

(issuer can prepay future sinking fund installments)

You are mapping:

How predictable is principal return?

How exposed am I to final-day default?

How much optionality does the issuer own?

8. Value Investor Interpretation

To a value investor, the sinking fund provision reveals the bond’s character.

If the sinking fund is strong and clear:

- Risk declines over time

- Recovery rates improve

- Duration steadily shortens

- Many downside outcomes are softened

If the sinking fund is weak or discretionary

- Optionality favors issuer

- Redemption can be timed against investor

- Yield-to-maturity becomes unreliable

If there is no sinking fund (pure bullet)

- Maximum exposure

- Maximum loss severity

- Duration is fixed

- Yield should compensate for concentrated risk

Conclusion

Principal structure — not coupon — often determines the true risk of a bond.

A 6% coupon on a heavily amortizing or sinking-fund bond is safer than a 6% coupon on a pure bullet maturity, because the risk density is completely different.

Understanding amortization and sinking funds lets you see where:

- Default risk declines

- Issuer optionality increases

- Investor reinvestment risk emerges

- Duration silently shifts

Most importantly, it lets you evaluate credit the way professionals do:

By asking how much risk remains at every point in time, not just at final maturity.

Next in the Series

Post #6 — The Event Risk Section: Change-of-Control, Ratings Triggers & Covenant Traps

This will cover:

- Change-of-control puts

- Ratings downgrade provisions

- Tax/event redemption clauses

- Why these sections save investors in mergers and LBOs

Leave a comment