Series: How to Read a Bond Indenture — A Value Investor’s Framework

Introduction

Most bond investors focus on yield. Savvy, downside-oriented investors focus on where they sit in the capital structure and what supports their claim. In other words: seniority and security.

If the company blows up, how much of its assets are legally available to you and how many creditors are ahead of you? That’s what determines how much you might recover.

This post walks through how to evaluate seniority, secured vs unsecured debt, structural subordination, and intercreditor risk using Ford Motor Company as a concrete example.

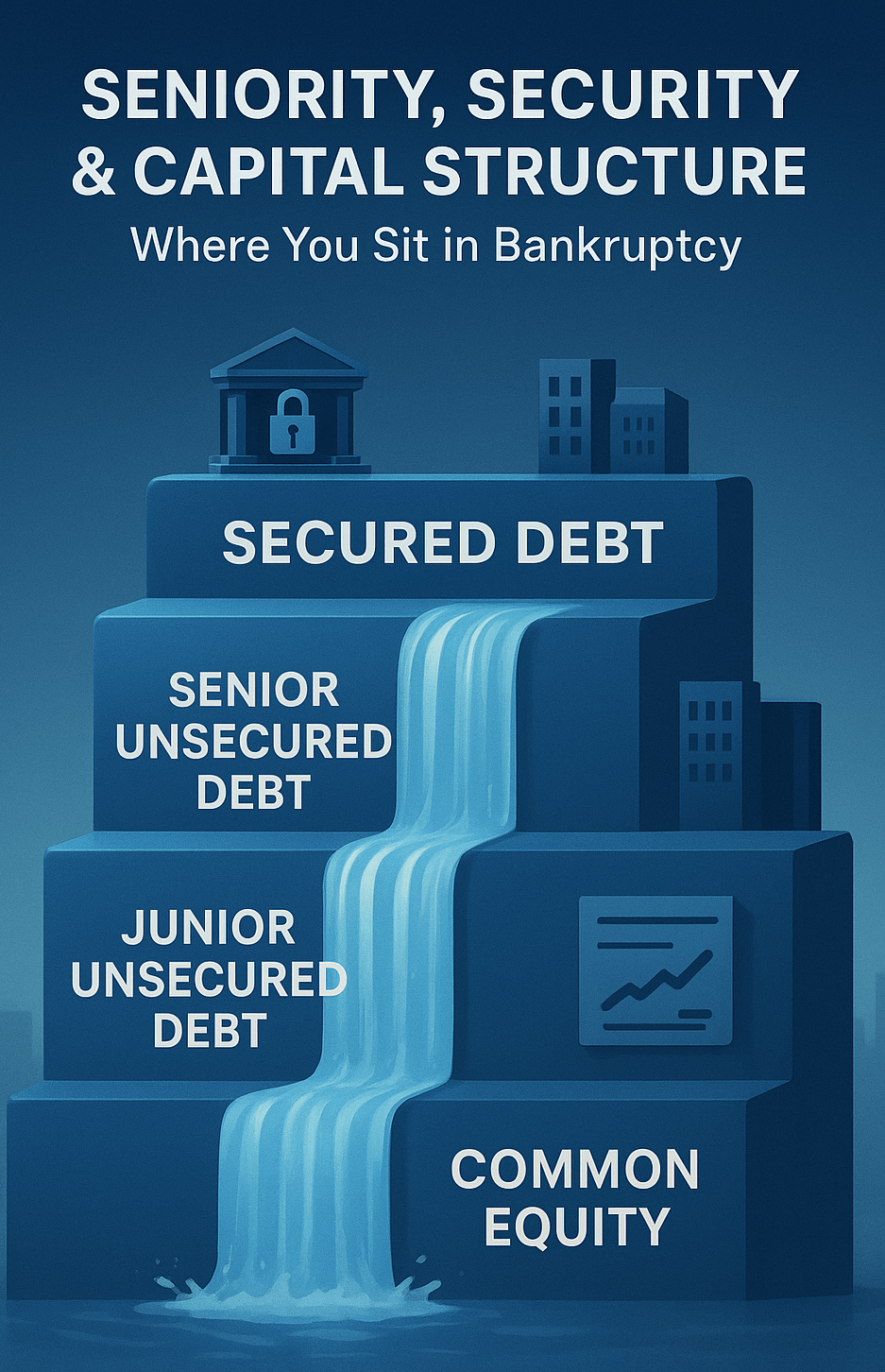

1. The Capital Structure: A Bankruptcy Waterfall

When a company fails, there’s a legal pecking order for claims. Here’s a simplified but realistic waterfall:

| Priority | Class | Example | Paid When? |

|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | Secured Debt | Bank loans, asset-backed debt | First — from specific pledged assets |

| #2 | Senior Unsecured Debt | Corporate debentures (unsecured) | After secured creditors |

| #3 | Subordinated / Junior Bonds | High yield / mezzanine debt | After senior unsecured debt |

| #4 | Convertible Bonds | Debt that can turn into equity | Depends on structure |

| #5 | Preferred Equity | Preferred shares | After all debt |

| #6 | Common Equity | Shareholders | Last in line |

Why this matters: As a bondholder, understanding your place in this hierarchy is critical. If you hold senior unsecured bonds, you are ahead of many creditors but still behind secured lenders.

2. Secured vs Unsecured: What Actually Backs the Bond

- Secured Debt is backed by specific assets (like factories, receivables, or other tangible property). In a liquidation, secured lenders often have first claim on those assets.

- Unsecured Debt (Debentures) has no claim on specific assets. These creditors rely on the issuer’s general creditworthiness and are paid only after any secured debt is satisfied.

Many corporate debentures are unsecured, meaning bondholders don’t have a claim to particular property. Their protection comes from the company’s credit profile and its indenture covenant structure.

3. Structural Subordination: HoldCo vs OpCo Debt

Not all debt issued by a company is created equal where the debt is issued matters:

Suppose a company has this structure:

HoldCo (Parent Company)

▲

│

OpCo (Operating Subsidiary)

- OpCo Debt: Debt issued at the operating subsidiary level typically has direct access to operating assets and cash flows.

- HoldCo Debt: Debt issued by the parent company (HoldCo) may not have a direct claim on operating assets. Instead, HoldCo bondholders rely on dividends or upstream cash flows from its subsidiaries.

If you hold HoldCo debt, you might be structurally subordinated to OpCo debt meaning even “senior” bonds at the parent level could get paid only after a subsidiary’s debt is settled.

4. Intercreditor Agreements & Pari Passu Clauses

Even bonds with the same “senior unsecured” label can be unequal in terms of legal priority. Two key concepts here:

- Pari Passu: Means “on equal footing.” Debt that’s pari passu ranks equally, but this doesn’t necessarily mean equal recovery — structure and guarantees matter.

- Intercreditor Agreement: A contract between different creditors that defines who has priority, how collateral is shared, and who gets paid first under certain conditions.

Also important: guarantees. Sometimes subsidiaries guarantee debt, which can improve recovery prospects. But whether these guarantees are “full,” “limited,” or “structural” depends entirely on the indenture.

5. What to Physically Look for in the Indenture

When analyzing a bond’s indenture for these structural elements, pay close attention to:

- The “Ranking of the Notes” section — describes whether the bond is senior, subordinated, secured, or unsecured.

- The “Security Interest” clause — what assets are pledged, if any.

- Guarantees — which subsidiaries or entities guarantee repayment.

- Limitations on Liens — whether the issuer is restricted from creating new secured debt that would rank ahead of existing debtholders.

- Intercreditor Agreements — if there are multiple creditor classes, how their rights interrelate.

If these sections are vague or missing, that’s a red flag: you may be taking on unseen structural risk.

6. Real-World Example: Ford Motor Company

Let’s walk through Ford’s indenture structure to illustrate these concepts:

- According to Ford’s indenture (for its 2062 Notes), the notes are unsecured obligations.

- These “senior debt securities” are ranked equally with Ford’s other unsecured, unsubordinated debt at the parent company level.

- Limitation on Liens: Ford restricts its ability to pledge core U.S. plants as collateral unless certain thresholds are met.

- Specifically, the indenture says Ford cannot guarantee other debt secured by its principal U.S. plants unless that secured debt is “equal and ratable.”

- That said, the restriction only activates once Ford’s secured debt (plus discounted rent obligations) exceeds 5% of its consolidated net tangible automotive assets.

- On the corporate side, Ford’s credit facilities (revolving credit, etc.) are unsecured, but important: certain subsidiaries provide unsecured guarantees if Ford’s senior unsecured long-term rating slips below investment grade.

- In its 2023 annual report, Ford notes that these sub-entity guarantees were released after its senior unsecured long-term debt regained an investment grade rating.

Interpretation (Value-Investor Lens):

- Ford’s bonds are unsecured, so as a bondholder, you don’t expect to have direct claim on plants or physical assets.

- The limitation on liens clause gives some protection, but it’s conditional: only kicks in above a defined secured-debt threshold.

- Structural risk is non-trivial: subsidiaries guarantee debt in certain stress scenarios, but those guarantees are conditional on rating triggers not automatic.

- That means bondholders need to evaluate Ford’s credit strength, rating triggers, and how likely secured debt could dilute their recovery in a worst-case scenario.

7. Why This Matters for Value Investors

- Risk + Recovery: If bonds are unsecured, you must assess how much is left after secured debt in a bad outcome.

- Optionality: Understanding guarantee triggers (like rating-based guarantees) helps you gauge how much upstream cash-flow risk you’re exposed to.

- Covenant Leverage: Knowing structural subordination lets you demand better protective covenants elsewhere (in other bonds).

- Yield Justification: Higher yield may reflect not just credit risk, but also subordinate structure or lack of security.

8. Next in the Series

Post #3 — Negative Covenants: How Indentures Protect You From Managerial Value Extraction

In that article, we’ll dive into how debt agreements explicitly restrict what management can do with cash and assets and why that matters for bondholders’ safety.

Leave a comment